Of the few untold stories of my life, the one involving the most beautiful snake I have ever encountered on Indian soil is not an easy one to write. Though my friend and co-conspirator in this adventure, Ashok Captain wrote ‘The Barta Chronicles’ for Hornbill – the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) magazine in 2010, my account of the story remained untold till now for several reasons.

That was probably the last unencumbered adventure that I had before the momentum of my life changed for a decade. I was busy either fighting, running away from, or solving puzzles created by the process called living.

It was the night of 16th May 2006, when I reached Itanagar, I had no clue about what was in store for me for the next two weeks. I had taken ten days urgent leave from my job at Sumitomo Chemicals, where I handled their Environmental Health Division, to help my friend Asit Biswas of Help Tourism, handle the entire logistics involved in producing an Animal Planet Documentary titled, ‘When the Bamboo Flowers’.

Sometimes during the filming process, a story needs to be changed to accommodate some new findings or an interesting angle, and that was what happened during the production of ‘When the Bamboo Flowers’. While covering the flowering of bamboo and its impact on communities in North East India, whispers of a snake associated with the bamboo flowering were heard. The production unit desperately wanted someone who could help explore that angle. As Asit knew I worked with snakes, he called me for advice and I had suggested Ashok Captain’s name, but to get Ashok anywhere, needs a lot of planning as he hates impromptu actions. I haven’t seen such a detailed planner as Ashok; his pathological attention to detail, and to plan for every possible eventuality had helped us later on during a major part of this story. To begin with, the filming unit needed an expert ASAP. As a reply to an SOS sent by Asit, I arrived in Itanagar.

So there I was, at Hotel Arun Subansiri in Itanagar, trying to get some sleep before my journey into the unknown. My assignment was to search for a snake, called a Barta by the local Nyishi community. As per folklore, when the bamboo flowers, the number of rats increase and that’s when this deadly snake appears. Other than this folk tale I didn’t have a clue about the snakes found in that region. I had many apprehensions, the foremost being that I wouldn’t find any facts about this story and I would probably just roam around and return empty-handed from an ‘all expenses paid’ 10-day vacation.

The production unit had camped at a place called Leporiang in Sagalee circle. My route passed through Doimukh, Kheel, Sagalee and then on to Leporiang. If one is new to the Arunachal jungles, as I was at that time, the experience dwarfs you. The scale of the forest is so far beyond one’s physical reach that one is forced to open one’s mind to absorb its vastness. All one’s rushing to doing things, the excitement of adventure or confidence of being in control gets lost in those mountains and valleys of pristine rainforests. One truly becomes a small part of this system which we call Nature.

The road to Leporiang was washed away by rain, a little before the village. So I walked the last kilometre after crossing a river on foot and reached the Public Works Department Inspection Bungalow (PWDIB), the base for me as well as the film crew. Asit was there to meet me and he had already arranged a tent for my stay. The PWDIB. was a store and support staff quarters, and a few tents have been pitched in the compound. These served as living quarters for some of us. As the time was crucial as well as costly for the team, we immediately had a meeting with Arun Kumar who was director, Alphonse Roy, the cinematographer, Asit who handled all logistics and me to decide on a plan of action.

The team was filming the story of bamboo flowering and the famine that follows, at Leporiang in Arunachal Pradesh and another place in Mizoram. Bamboo flowering is taken as a bad omen in many of the north-eastern tribal communities. According to ancient beliefs within tribal communities, when the bamboo flowers, there is death and destruction that follows. It is said that when the bamboo flowers, a plague of black rats invariably follow and once the flowering ends the whole population of rats converge on granaries and paddy fields to finish them off and this results in a famine. Bamboo flowers at the same time across its geographical range depending on the species and after flowering, it dies. So one also loses vast tracts of bamboo from the land. Bamboo plays a role in north-east India similar to that of the coconut tree in the southern and coastal India. There are more than a thousand uses of bamboo in tribal cultures; these range from food, shelter, to make tools, bamboo is used everywhere. Bamboo flowers once in 48-50 years, depending on the species.

Though I don’t believe in the resulting famine, there is a scientific logic in understanding the relationship between the flowering of the bamboo and an increase in the population of rats. Bamboo flowering en masse is one method of ‘predator satiation’ so that a greater number of seeds survive. When there is a huge volume of prey, predators cannot eat everything and large numbers of prey survive. To balance the increased availability of food, the population of the predator (in this case rats) increases by their reproductive cycle going into overdrive. As a reaction to the windfall of seeds after the bamboo flowers, the rat population increases as well. There is always a cascading effect in nature, everything is linked to everything else.

Historical records show that when the last time the bamboo flowered was in 1958-59 and there was the loss of property and crops. This resulted in the deaths of several people. It was estimated that around 2 million rats were killed then as a result of a bounty of 40 paise being placed on each rat killed. Some analysts even say that the Mizo National Famine Front set up in 1958 became the Mizo National Front and resulted in a bitter separatists’ struggle which ended in 1986. With this background of bamboo flowering, it wasn’t any surprise that the film crew were there in 2006 – which was the year the bamboo was due to flower. At Leporiang, the story rose another level from the bamboo flowering and the consequent outbreak of rats; the locals maintained that once the rat population increased, a snake called the Barta appeared on the scene and they feared the snake far more than the famine that came after the bamboo had flowered!

That’s how I ended up in Leporiang – to determine if the legendary Barta was indeed a real snake. I was given carte blanche to chalk out an action plan. Looking at the terrain and scale of the forests, I decided to concentrate on the local people first for any clue and information on the snake. At the time I wasn’t even sure if such a snake existed. With the help of Diyu Tomo, Asit’s local collaborator and Nabam Radhe an educated Nyishi lad, I invited the Gaon Burahs (GBs) of the surrounding villages for lunch the next day.

Once the first step was taken care of I started working on my field kit for the next 7 days, as I was going to be on my own; snake stick, restraining tubes, snake bags, Smith’s ‘Serpentes Volume III, the Fauna of British India’, Rom Whitaker and Ashok’s ‘Snakes of India, the field guide’, leech guards, a raincoat, insect repellent, camera gear, some emergency rations and most important of all, I learnt a word for ‘Thank you’ in the Nyishi language, ‘Paya Lingcho’.

While I was doing this in my tent I heard a commotion outside. Radhe came running with the news of a snake that the villagers had found and that it could be Barta. With considerable excitement and anticipation, the film crew and I reached a place where all the villagers of Leporiang had gathered. To the disappointment of the film crew, but my happiness, we found a Monocellate Cobra, stuck in a net at the village playground.

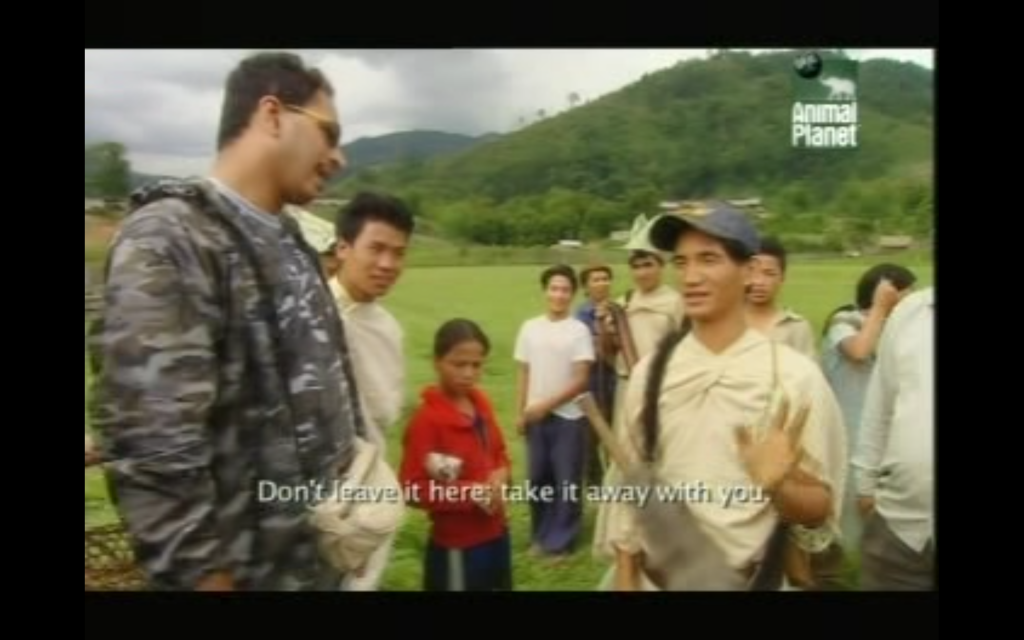

The Nyishi tribe are excellent hunters and everyone carries a heavy-duty machete with a bamboo handle called a dao. Here I was with twenty-odd dao-wielding men who were animatedly discussing how to kill that poor snake. It took me quite some time to convince them that there was no need to kill it and that I would instead, catch the snake and take it away from their village. It was such a beautiful individual. After disentangling the snake from the net, I bagged it in the snake bag which I had carried along. It was almost 5.30 pm by then and as the light had faded, we decided to release the snake next day morning when the filming could also be done. Two Nyishi lads came with me till the tent to ensure that I was taking snake with me and not releasing it anywhere close-by. I spent the first night at Leporiang with a bagged Monocellate Cobra kept under an inverted bucket with two field guides on top of the bucket for weight, close to my sleeping bag.

When I woke up and got ready the next morning there was already a crowd of excited villagers gathered in front of the PWDIB, thanks to the Monocellate Cobra incident of the previous day. Possibly saving an animal was a harder and more courageous feat than killing it, in the minds of those who were born hunters. That one incident was enough to break the ice with the local community. So the first job of the day was to take the Monocellate Cobra very far from Leporiang and release it. Though the people had demanded that I release it 100 km away, a cameraman and I got a lift in a vehicle which was going to Sagalee, 33 km away to get rations. I released the snake en route with heartfelt gratitude as it had helped me make friends with the locals.

On my return from Sagalee, I found about 14 Gaon Burahs of the surrounding villages waiting for me, all were wearing the red coats given to them by the government as a symbol of authority. Gaon Burahs play the role of policeman, judge and conduct other administrative duties in their respective villages. It wasn’t a male-dominated field though, during my search for the Barta, I found several of the Nyishi villages had women Gaon Burahs. That’s what I love about our tribal cultures, many of them have women dominated communities. All the Gaon Burahs were very quiet and I wasn’t sure how to start a conversation with them. But my quandary proved baseless. As soon as I said Barta, the atmosphere changed and resulted in all fourteen of them talking animatedly at the same time. I needed the collective help of Radhe and Diyu to get some coherent information out of that discussion. I gathered that Bartas were found ‘everywhere’ and that many deaths had occurred due to their bites, people had died immediately or after a day, if one looked into the eyes of a Barta, it followed the person home and killed him or her. It’s a huge black snake with blue and yellow markings; they kill it with a long bamboo and chop its head off, then throw the body and head in opposite directions because they think that it is immortal and can ‘take revenge’ if the head and body come together again. A trader came there every year to buy pickled Barta heads! All of them claimed to have killed a Barta in their fields the previous month and that they could show me the dead body of a Barta if I accompanied them to their fields.

After processing all the information, I decided to visit some of the fields with them. At that time, I didn’t know that in Arunachal Pradesh, a field meant a cleared patch of land, somewhere deep in the forests for jhum kheti (slash and burn cultivation). I also decided to follow up on the information of the trader who came to buy pickled Barta heads. So the next three days were spent travelling from one jhum kheti to another. Later in the evening, I met some traders at Sagalee to see if anybody had pickled Barta heads. After visiting 10 jhum khetis (which proved to be backbreaking work) and trying to find pickled Barta heads in the evenings, I concluded that this might not be the best way to locate a Barta as the last one anybody has seen was approximately 30 years ago and that too it was a vague piece of information. Jhum kheti treks also reminded me that in these cultures, time does not have any measurable value, anything ‘recent’ can range from 20 years to 1 month ago, hence it was of no use to follow these reports. That evening I requested Radhe to take me to a local hunters’ gathering. These are typical tribal gatherings where the tongue gets loosened with some local alcohol, in this part it was apong, a rice beer. Out of the many Barta stories I gathered that day, one was out of this world yet plausible. An old hunter told me that his father used to collect King Cobra eggs from nests and place them around his jhum kheti and home as protection against Bartas; he probably knew that King Cobras eat other snakes. I was not there to judge tribal wisdom, which certainly had far more knowledge about the local natural history than I did.

I also noted two promising leads which were important in my quest for the Barta. I was told that there was a Shaman (local healer) in Rachi village who had a Barta skin with him and that the village of Sango has more Bartas than any other village around. I took these stories with a pinch of salt, or rather a pitcher of Apong. Even though I was sceptical we left for Rachi on foot the next day. It was around three hours walk through terrain that was manageable for me. As soon as I entered the hut of the Shaman, I was surprised to see an aristocratic old couple sitting on an elevated platform in front of the door. I felt like Indiana Jones entering a remote tribal village. Radhe introduced me and translated my questions for them. The first question I asked was, how old were they, and the answer was, they have seen two bamboo flowerings, that meant that they were about 95 to 100 years old. Radhe showed them a lot of respect and wasn’t willing to ask them too many questions, so I restricted my questions to the Barta skin which I had heard about. I got to know that their elder son, who was the next in line to become the Shaman, had the skin. I respectfully said Paya Lingcho to them which got me a faint smile from them both and left their home.

The son, who was also a village elder, was staying in a nearby longhouse. He was more practical in his approach as he was under the influence of Apong and spread his hand in front of me while smiling at me. I offered him a 100 rupee note and was rewarded by him executing some wild dance moves while he brandished his dao. Suddenly it struck me that the sheath of his dao was covered with snakeskin. I excitedly asked him if I could see his dao. He smiled and unwound the entire skin from the dao and gave it to me to inspect. I touched it like I was touching the most precious thing in my life. It was around 6 feet in length minus the head.

As it had been smoked, I could only see a black and white body pattern on the skin. My initial thought was that it was a King Cobra as that’s the only large snake with a black and white pattern known from this region. I tried to count the scales around the body (dorsal scale rows), but this proved impossible as there were many breaks in the skin. After a little more prodding the Shaman’s son removed three fangs from a small pouch that he wore around his neck. They were perfect solenoglyph fangs; these hinged, erectile fangs are the business-end of the most advanced venom delivery system in the world and are exclusive to vipers. Finally, here was proof that the Barta existed –a six-foot-long skin and large viperid fangs. The Barta was either a huge viper unknown to science or a subspecies of an existing viper. The evidence had me completely flummoxed. On the brighter side, at least I now knew that the Barta was a real snake, now I only needed to find an entire and preferably live individual.

By the time we returned to Leporiang with footage of the skin, fangs and the Shaman’s son’s wild dance, the heavens had opened up with lightning and buckets of rain. It was also time for the majority of the film crew to leave for Mizoram where the bamboo was flowering. So a young cameraman, Basab Mallick, was left with me along with Shishir from Asit’s team and Radhe as my support team. Our next plan was to reach Sango, which was uphill from Leporiang and about four hours away by my ‘walking standards’. Though Radhe said that it would take forty to fifty minutes, I added another three hours to his local and ridiculously optimistic estimate. And I was so right, after twenty or thirty leeches and four and a half hours of climbing, I reached Sango in a completely exhausted state. We were put up in a local school, which had two classrooms and was closed for the vacations. There was a broken Indian-style toilet attached to the school, so one had to choose between battling the local pigs, if one ‘went’ outdoors, or brave being seen by the whole village. After much deliberation, I opted to spar with the pigs. Interested readers can read about the finer details of this exercise in my blog “How to Shit in the Wild”

After discussions with the elders of Sango and their Gaon Burah, Nabam Hanya, we decided to go to the sites where Bartas had recently been killed. So for the next two days, I went up and down in treacherous terrain with the help of two bamboo walking sticks. On the first day, while walking and slipping through some muddy slopes and thick undergrowth, I chanced upon a Burmese Glass Snake, not a snake but a legless lizard of the genus Dopasia, earlier known as Ophisaurus. Such an amazing beauty!! It made my day and I had started to feel optimistic after I had photographed it. While roaming in those parts, I was able to photograph numerous butterflies, it was heaven for ‘butterflying’ even for one were not particularly interested in butterflies. On the second day, we reached a jhum kheti, where our host pointed to a dead snake from far away. I walked closer to the remains of the snake and was astonished to see a half decomposed body of a headless, blue, green and yellow snake. It wasn’t possible to identify it with just these remains, but this certainly confirmed that its colouration matched the descriptions that I’d been given. I was on the lookout for a large viper that was blue, green and yellow! I thought of other pit vipers like the Jerdon’s Pit Viper found in this region, but the colours were different and I’d never heard of them growing this large. Though it seemed like we might find a Barta in Sango, we only had two days in which to do this.

As time was short, I asked Radhe to enlist the help of some local hunters who could go out and search for Bartas with us. In this way, we could cover a greater area in the two days that we had left. One day passed without any positive developments and on the second day, I woke up feeling dejected and started to pack my rucksack as we were to leave after lunch for Leporiang. In that gloomy mood, I heard someone shout Barta and everything got galvanised in my brain, I ran towards the end of the village where the children were shouting from. The sight will remain etched in my memory forever. I could see Tachang Nypo, a local Nyishi hunter, walking towards the village with a large bamboo on his shoulder. The front of the bamboo had something snake-like tied to it. Nypo had found the snake three hills and a valley away, trapped it using a bamboo snare and carried it on his shoulder to bring it back to the village. I didn’t have my camera with me as I ran towards him with only my snake-stick. I hoped that Basab was there to film the whole scene. He was, God bless him! I asked Nypo to put the bamboo down, which he immediately did and moved back quickly. I moved forward with the snake-stick in hand, pinned down the huge head of the snake and caught it behind its neck. I asked Nypo to cut it loose from the bamboo snare, which he did with one swift movement of his dao. I lifted the snake and for the first time looked at it as a whole. And here I had in my hands, the most beautiful snake I had ever seen! All the descriptions that I had heard from the Nyishis were spot on. Other than a small injury on its lower jaw and some mud on its head, the snake was unharmed, which was amazing considering their fear of this snake. For Nypo it must’ve been a monumental task to bring the snake back alive. All the credit of finding this specimen goes to the hunters of the Sango Basti!

Once the initial excitement died down, I cleaned up the snake before put it into restraining tubes for further studies. Once the scale counts were completed and the snake was photographed, I quietly walked away from Sango for half an hour in the direction of a nearby stream and released the individual close to the buttress roots of a large tree and returned to Sango. I was worried that people would want to kill the snake but when I told them that I had released it back into the wild, they were fine with it. Hanya, the Gaon Burah told me that, once they saw me handling the snake, their fear lessened considerably. I wasn’t sure whether this development was good or bad at the time. We didn’t have permission to collect any specimens on this trip, hence I couldn’t collect a specimen then. I left Sango with a promise to myself that I would return soon with the necessary permissions to further study this snake.

My field notes from this trip other than scale counts are given below:

Barta seems to be a large pit viper, on its dorsal side it has an intricate pattern of black, blue and yellow, the ventral side has a beautiful yellow and blue pattern. It wasn’t aggressive in behaviour but puff its throat when approached . As per local information, it may be an arboreal snake or living within tree buttresses and lay eggs. So the Barta was a beautiful large pit viper which laid eggs!

This first trip to Leporiang and Sango gave me a lot to ponder upon as well it resulted in my making new friends. Nabam Radhe was phenomenal in his approach to support us responsibly without going overboard while also making us follow tribal norms and culture. I had seen Alphonse Roy’s documentaries of Big Cats of India. But while working with him in these leech and Damdum-infested forests, I admired him and the professionalism of his team while filming in such adverse conditions. We only see polished films on screen, but the hard work it takes to make such films is beyond words. Hats off to the whole team of ‘When the Bamboo Flowers’. Alphonse became a dear friend over the years and still keeps me motivated me with his quality of work.

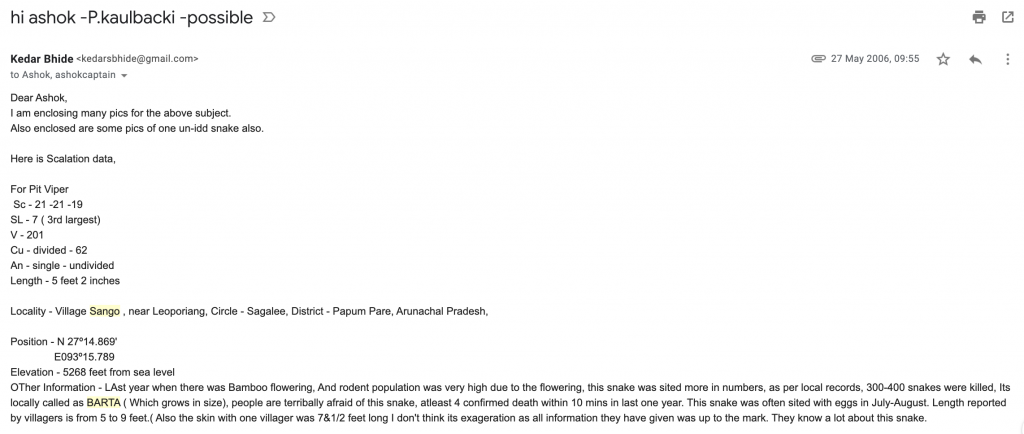

As I got back to Mumbai, I wrote to Ashok Captain with the primary scalation data and images. Though I wasn’t certain about the identification, I could confidently say that the snake was close to Protobothrops kaulbacki, but had a different number of mid-body scales.

Ashok was very excited by my findings. We met several times at the BNHS and had discussed a possible plan of action over toxic-looking Triple Fried Rice at the Udipi-managed restaurant – Aamdar Niwas opposite the BNHS. Those were the days when, Ashok, Varad Giri and I were planning to start ‘Triple Fried Rice Productions’ to give a face to our dreamy discussions on Indian herpetology. Meanwhile, Ashok introduced me to two pit viper experts from Germany, Andreas Gumprecht and Frank Tillack. Both had co-authored a beautiful book on Asian Pitvipers along with two Russians and Ashok. We e-mailed them my initial findings and their excitement was evident in their replies. The production team of ‘When the Bamboo Flowers’ was also very excited as they needed a name for the Barta before they telecast film on Animal Planet.

We decided to go to Sango as soon as possible. The first challenge was to find funding for our expedition. This time Asit came to our rescue, through his NGO arm ACT (Association for Conservation and Tourism), he offered complete logistic support on the ground, once we reached Itanagar. We were on seventh heaven; with Asit Biswas, Shishir Adhikari, Diyu Tomo and Radhe Nabam handling all our logistic and administrative requirements it meant that Ashok and I were free to concentrate on fieldwork. My frequent-flier miles also helped get us both to Guwahati. We got in touch with our friend Bharat Bhatt of the State Forest Research Institute (SFRI) at Itanagar. Bharat immediately agreed to join us on the expedition. Finally, our Barta team was ready for action! Every member of the team was invaluable for finding the Barta and taking the story to its logical conclusion.

By the time we reached Leporiang on 3rd August 2006, after crossing multiple landslides on the road, it was afternoon. It took us more than eight hours to cross 130 km. The news of the return of the Barta team had spread like wildfire. My old friends and some new ones were waiting at the PWDIB to meet us. We were informed about two black snakes they had seen sitting on heaps of bamboo leaves nearby. Ashok and I looked at each other and smiled, thinking about how it was the dream of most herpetologists to see two King Cobras on their nests in the Western Ghats, but here in Arunachal, it was a common sight. As we were focussed only on finding Bartas we took the GPS locations of the nests, which were 50 meters apart from each other and a couple of shots of the Queen sitting on one of the nests, we didn’t disturb the snakes and left them to guard their nests. King Cobras are the only species of snake which build nests. They do this by heaping together dry bamboo leaves using their body coils. The female King Cobra guards the nest till just before the eggs are due to hatch. After this, she leaves the nest, perhaps not wanting her natural cannibalistic instincts to be a threat to her young. This incident reminded me of the story of the old Nyishi hunter taking King Cobra eggs and leaving them in the Barta’s territory. Looking at these two nests in close proximity to the village and the way the locals treat them without destroying them, my belief in their story was strengthened.

The next morning we set forth for Sango. We met an elderly lady coming down from Sango, as we waited for some team members just outside Leporiang. We started chatting with the lady, asking about our friends and their families in Sango. As the discussions progressed, she suddenly said in a sombre tone, “Don’t go into mountains looking for Bartas, if you do, you won’t return alive”! Though that might not have been exactly translated by Radhe, I was taken aback. Before I had started from my home in Mumbai, we had a small get-together, and I had jokingly said that, if I were to get bitten by a Barta, probably only my death certificate would come back. Who would carry a body back from such a remote area! Now I was cursing myself for those statements made in jest. Once again, Ashok and I went over our safe handling protocols, to be doubly sure, just in case we found a Barta.

We reached Sango with a fair amount of leech and dam-dums bites that were routine in these parts. I was very happy to meet Hanya, Nypo, Takap & Tayang again. They were perfect Nyishi elders, master of their hunting craft, expert trap makers, all with large families and at complete ease in their rain forest environment. I remember their stories of an annual Aconite hunt which they had shared with me on my earlier trip. Beyond Sango, it’s ‘no man’s land’. There are no villages, even if one walks for two or three days. These hunters go there in groups every year to get Aconite plants to prepare poison for their arrows. They have told me stories of a blue lake, which one reaches after three days of walking and how they camp alongside the lake and how many Bartas they have seen and killed on their way.

The best way to enjoy these stories is to keep one’s ‘contaminated urban educated’ logic closed within one’s self. I’ve learnt to keep my thought processes neutral and not judge these tribal cultures on a fixed scale of good or bad. In the same way, when I was in their longhouse, I had refrained from asking what they had served me because if I knew what it was, I probably wouldn’t have eaten it. I neither wanted to insult them nor did I want to become so involved as to be a part of their tribe. I was just a guest and I wanted to remain as a guest. When I look back now, I think that I probably wouldn’t have survived if I had tried to be part of their tribe.

This time our accommodation was in Tana Sarah’s longhouse. She was the lady Gaon Burah of Sango. These longhouses are made on bamboo platforms eight to ten feet above the ground. There are no partitions in the longhouse but each family has a separate fireplace. Four to five families stay together in one longhouse. Below the longhouse is a place for their pigs and poultry. Sarah was fascinated with my binoculars and every day she asked for them and scanned the forests looking for something or someone in the direction of ‘no man’s land’. There was possibly a story there from her past, but I wasn’t able to get her to share it with me. The Nyishis of Sango were very pragmatic people and disliked talking about their past. That evening we met with the village elders. I had made photo prints from my earlier trip and gave each of them their respective photos. During this meeting, we decided on an action plan. Nypo and Takap had seen two Barta nests in the forests and thought that the mother would be nearby, as they have seen Bartas guarding their eggs clutches many times before.

So next day we left our longhouse with four Nyishi hunters as bodyguards ready to protect us with their guns, bows & arrows. As Nypo guided us to the Barta nest, I was ready with my cameras to record everything. An hour later we reached a heap of dead logs near a stream. All the hunters were ready for action as Nypo showed me a clutch of eggs below a rotting log. There was no sign of the mother anywhere nearby. We searched for almost an hour. I photographed the Barta eggs with Hanya and Tayang standing guard on either side of me. This was the first time ever that I had photographed anything with two gunmen protecting me! The eggs reminded me that Kaulback’s Pit Viper lays eggs and Jerdon’s Pit Viper (a similar-looking species) bears live young.

We continued our search further north. By noon we reached an abandoned jhum kheti where the forest had tried to reclaim the clearing. All that remained was a small bamboo platform. I spent time photographing the butterflies and insects that were around me. In doing so, I got bitten by some insects on my hands. Both my hands were swollen. I sat uncomfortably on that bamboo platform, lost in my thoughts, while the others rested. In that tired and painful state, I contemplated leaving everything in my life behind and retiring to Sango to spend the rest of my life. Sometimes life shows you a mirror to reflect in at the most unexpected of places. Nabam Gongma, the eldest of all the Nyishis who had accompanied us, suddenly came and sat next to me and offered me a piece of honeycomb to chew. I couldn’t possibly refuse. He instructed me to take a bite and then to chew on it until only the wax remained, before spitting it out. It was pure sweet ecstasy, I don’t think I’ve ever had a similar experience either before or after this. The day ended without any Bartas; I also cancelled my plan to retire in Sango!

We returned to our host Sarah’s longhouse. After a hot meal beside the fire, we washed our hands in the holes on the floor, next to the fire. As a practice, all scraps and dirt are washed down through these holes. The pigs wait below to polish off everything that reaches them. It was a very clean arrangement until one attempted to sleep. Once one settled into one’s sleeping space and the night took over, all the fleas, ticks, mosquitoes and flies, which are on the pigs and poultry below, migrate upward to the fire and the noises that these pigs make with their stomachs full, are not the most melodious tunes to put one to sleep.

The next day we decided to go east, towards the Papum Pare river. The route was down a steep slope. This time, however, I was supported by carbon fibre trekking poles, which proved to be a blessing on those 80-degree muddy slopes. An hour and a half had gone by after we left in the morning. We entered a cloud forest and temperatures had fallen a bit. I could hear the sound of streams everywhere. Ashok was almost as physically fit as the Nyishi hunters and managed to keep up with the lead party, I trailed behind them by about twenty or thirty feet. Suddenly I heard a loud yell “Barta!” from the men below and I slid down those slopes to reach them as fast as possible. By the time I reached them, Nypo and Ashok had already caught the snake. This was fortunate as there was a deep, dark hole in the ground right behind it. After pinning the head, Ashok caught its head and using both hands, lifted it off the ground. I held out the snake-bag which was clipped to a degutted badminton racket. As soon as he threw the snake into the bag, I twisted the racket and put it down on the ground. Ashok pressed the snake stick over the twisted part of the bag so that the snake couldn’t escape and once he’d done this, I unclipped the snake-bag from the racket and twisted it further before tying its neck in a ‘U’ shape. Once the initial bagging was done, we put the bag into a second snake-bag, tied it securely and transferred the double-bagged Barta into a red plastic bin that Bharat had carried. After this, I secured the lid of the bin with masking tape. This was a short-term arrangement; we would remove the Barta as soon as we got onto to flatter terrain, hence we were not worried that it would suffocate. The entire bagging operation, which had been rehearsed several times, was conducted in silence and took less than ten minutes. The snake was found in a hollow between the buttress roots of an Altingia tree. Shishir took some record photographs of the hunting party and we moved further down towards the Papum Pare river. Everybody was happy but silent as the surprise of getting a Barta so soon was thrilling. At the river, we exchanged our lunch packs with our Nyishi friends as a gesture of celebration. Shishir had packed chole–rice for us and Hanya and the other Nyishi gentlemen had their local rice and bhut jolokia (ghost chillies) wrapped in large leaves in their backpacks (which are made out of cane and are called Nara). That was my first experience with these chillies. The moment I bit into one, even though it was along with rice, I couldn’t close my mouth, I forgot all about the Barta, tears flowed out of my eyes like the Papum Pare river. Everybody laughed except me and once again Nabam Gongma came to my rescue. He went a little distance away and cut a piece of some bark with his dao, and told me to chew it. And within seconds my agony subsided, I soon got my taste buds back and my eyes returned to normal. I had fallen in love with those chillies and developed a taste for them over the last few years.

I wanted to take the snake out on the river bank to photograph it with the surrounding habitats, but Ashok and the others collectively voted me down. We returned to Sango with our prize catch. We took the snake out of the bags. Though Ashok had caught the snake, he was so busy with safety protocols that he had not seen the snake properly. Once the snake was out in open in that afternoon sunlight, I heard a collective gasp from Ashok and Bharat. The Barta had the same mesmerising effect on them as it had on me when I had seen it for the first time.

We photographed the snake, took scale counts and then followed the process of preservation to take the specimen back to SFRI. Though I don’t like collecting specimens, I understand that it is necessary for science. That evening there was a celebration at Sango. All the village residents came in their festive attire. Takap, Tayang & Nypo were in a fun mood and posed with us with their bows and arrows. All of us were sad to leave Sango and our Nyishi friends the next day. We took a group photo with the entire village before we left. We returned to Itanagar via Leporiang the next day. We had another celebration dinner at Itanagar with our team. As I returned to our room at the Hotel Arun Subansiri, I was taken aback to see Ashok booby-trapping the whole room with climbing ropes and water bottles. Our room was on the first floor with windows that opened onto a large terrace. He wanted to guard our CF cards as those were the only images of the Barta in the world!

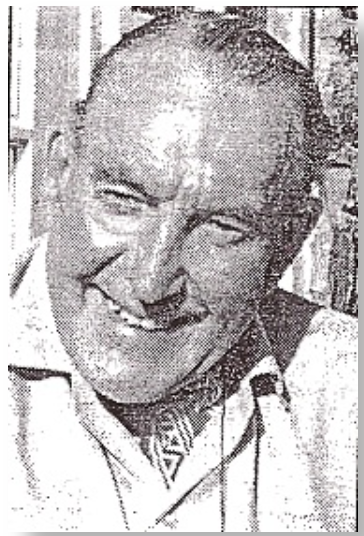

Next day we did further studies on the specimen at SFRI. Bharat assigned the specimen an official collection number and transferred it to the permanent collection of the State Forest Research Institute. Thus ended our trip. Ashok and I went to Itanagar once again in September, just for a day to confirm our scale counts as there were scale reductions at different places around the body. Frank Tillack compared our data with the BMNH (British Museum of Natural History) specimen and we concluded that the Barta was indeed Kaulback’s Lance-headed Pit Viper, Protobothrops kaulbacki. It was earlier known to science through a few specimens collected by Lt. Col. Ronald Kaulback from Upper Burma for the Natural History Museum, London in 1945.

Lt. Col. Ronald Kaulback had fascinated me after these Barta expeditions. Records showed that he fought against the Japanese army during the Second World War in Burma with his troops of Karen tribesmen and was successful in liquidating many of them. During his time in Burma, he collected specimens of snakes and lizards for the Natural History Museum. However, the most fascinating part for me was his travels in Tibet, as they coincided with my deep interest in travelling to Changthang, which is a part of the Tibetan plateau. He had travelled extensively in Tibet during the 1930s and wrote a book in 1934, titled ‘Tibetan Trek’. I had found a connection with him on two fronts viz. the Kaulback’s Lance-headed Pit Viper and the Tibetan plateau.

“When the Bamboo Flowers” was telecast on Animal Planet in November 2006, and that was the first public view the world had of this amazingly beautiful snake. I undertook a third expedition with Ashok, Bharat and Varad again in 2007 to Sango which resulted in no sightings of this snake. In recent years, the Barta has also been reported from other parts of Arunachal Pradesh. A road has been now cut from Leporiang to Sango, though not much has changed for the people of Sango and Leporiang. Bartas are still killed due to fear. In the end, we have only added a tiny bit of information to the history of the biodiversity of India.

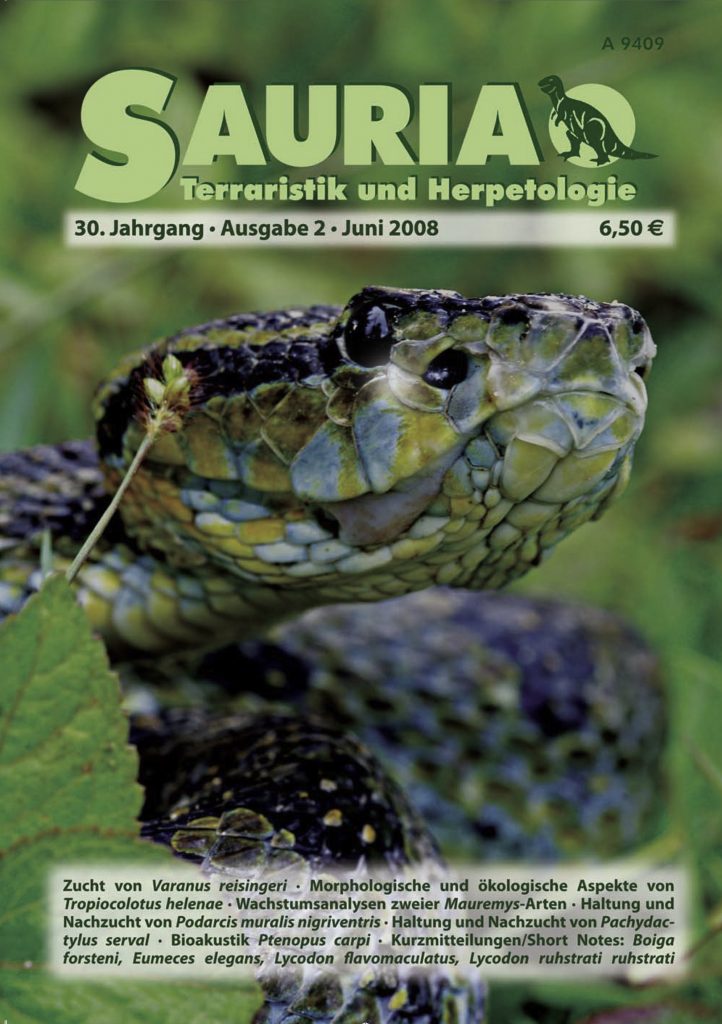

Our work was finally published as the first report of Protobothrops kaulbacki from India in Sauria, a German herpetological journal in June 2008. Further work is needed to study the Barta in detail and I hope that I can go back to Sango and do it myself.

I have to thank all those who supported the Barta Project –

Asit Biswas of Help Tourism supported and sponsored all local logistics. His team of Shishir Adhikari, drivers & cooks who took care of us.

The expeditions were impossible without Diyu Tomo, Nabam Radhe and all the Nyishi’s of Leporiang & Sango.

My friends, Ashok Captain, Varad Giri, and Bharat Bhatt were instrumental in all taxonomical work along with Frank Tillack and Andrea Gumprecht from Germany.

The team of ‘When Bamboo Flowers’ – Asoka Raina, Arun Kumar, Alphonse Roy & Basab Mallik.

These expeditions were serious emotional experiences for me and it has taken me many years to finally record my Barta experience.

The only physical expression that remains from these expeditions, is a permanent Barta tattoo on my right shoulder.

Paya Lingcho!

Great experiences narrated in a really flowing article. Keep up the great work!

Thanks Nitin

Love your work sir your naration to our barta was so true we do beleive that they take revenge even after cutting there heads off its good to know that in our place we have such a rare snake

Enjoyed reading about this once in a lifetime experience. What a journey! Kudos to entire team that got together for this expedition.

Thanks PK

Wow! Lovely article! Enjoyed reading it.

Thanks Anuj

Kedar, this is the most fascinating modern day adventure memoire I have read out of India in recent times. Please write more often!!!!!

Thanks Rajeev

What a fascinating narrative! This was like reading about explorations of yore, raw, full of uncertainty, the thrill of multiple hazards, and hardcore research. While the contribution of these ventures to herpetology is itself praiseworthy, I was also struck by other things in your blog: it is very humble and great of you to have acknowledged the part played by each and every individual in your team not only formally but as a part of your flowing narrative, your sharing of your own thoughts and feelings which made it poignant at times, and your sense of humour! Thanks, Kedar! Wonderful!! More to come I am sure…

Thanks Shantanu

Another beautifully penned memoir! I remember the Animal Planet documentary on the Bamboo flowering. The lockdown is really getting the best blogs out of you!!! Was hoping for a poem on it too 🙂

Dear kedar amazing work very interesting and detailed story whish I could do this kind of work .best wishes always

Before we get to Sango again, Kedar has really really gotta practice eating bamboo shoots. Varan – bhaat is all very well back home, but real jungle men ‘eat local’!

Now for the soppy stuff – I need to thank Kedar, the Nyishis of Sango, Asit, Tomo, Shishir, Nabang and Bharat for involving me in the ‘not-so-crazy’ jungle adventure. Paya Lingcho, Kedar.

Fascinating as always !! Happy for you kedarji

Exciting, incredible expedition. Thrilled to read. Best Wishes Kedar in ur endeavors.

Simply said, You are absolutely amazing Kedar! Didn’t know your writing and narration skills! Wish to visit with you some place.

Amazing.

Hi Kedar,

Ran into this by accident. What a time it was. Not that we seek credit but the first part of your journey and the discovery of the Barta was entirely coordinated and made possible by the Film Unit, which I was leading as Director. And the actual discovery, and a few other parts seem a bit fictionalised… the story, as recorded, is in the film and unused recordings @Discovery/Animal Planet. It was Directed by me and during Editing I have gone through the footage innumerable times. Agree it was a long, long time ago and memory does play tricks at times… this just got my memory jogged and hence this little note. Hope you are doing well. Stay safe and many more happy adventures.

Hi Arun, How are you ? you are not at all in touch , otherwise would have sent you the link . I have told Asok ji & Asit both to forward this to you but probably they have missed that. Also this story is about my journey with Barta which was longer that the film unit journey with it ( nearly 3 years ) . Yes all the credit goes to the film unit for initiating this journey to discover the story of Barta and when I say film unit, I talk about the whole team and I will be always grateful to the team. I also hope that my work has contributed to getting the final story. I have been truthful in most of this journey and much of the discovery part was during the time when the film unit has moved to Mizoram and I was with a lone cameraman. So probably you have missed that journey during those moments. But as you say it was a long long time ago and memory does play tricks at times —. Hope to connect with you again, be safe in these challenging time . Mail me kedarsbhide@gmail.com please. so I can reconnect.

Hey kedar, like I said there is no attempt at credit seeking. That journey was unique, at a last minute decision I asked for a snake expert. Convinced my Producer and Discovery. and the great story happened. I was convinced, over 2 trips, that what the villagers and radhe were saying was true…. this extension involved a lot of Ups & Downs with the Producers. I did insist, and Asit, who was my point-man in North-East then set the process in motion… Rest is your Story. A great Journey it was 🙂

Will mail you and we could catch up.

Sir, in our nearby villages there are Manny barta I love to see our barta thank you sir